A Tale of Two Learning Experiences

I don’t remember much of what I learned in high school.

I attended high school in one of the highest-ranked districts in the country in a wealthy suburb of Washington, DC.

Reciting the preamble to the constitution, I excelled. I could memorize the significant plot points in To Kill a Mockingbird and regurgitate them on multiple-choice tests: A+. The teacher-provided study guide helped. But, after the test, there wasn’t any incentive to convert that material to long-term memory.

In fact, one of my most prominent memories with a teacher in high school was when my history teacher told a joke. She said, “You know why we don’t make assumptions? Because to assume makes an ass out of you and me.” Our faces must have looked quizzical, so she spelled it out on the board:

ASS-U-ME

We sat obediently as her lips curved ever so slightly and she chuckled to herself.

Reflecting on my high school learning experience, I would describe it as teacher-centered, content-centered, and test-centered- teaching for teaching’s sake.

We were apt pupils. We learned early on that the surest way to meet a competency was to act as if we were learning.

My first year in college at the Rhode Island School of Design, I was in English class. My teacher always arranged the desks in a circle. Rather than standing at the front of the room, he always sat at a desk in the circle. He had just assigned us a paper on The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Feeling bold, I raised my hand and let him know that I hated the book and thought Benjamin Franklin was a pompous ass, and I wouldn’t be writing any essay to sing his praises. I wasn’t sure how he would react. He nodded thoughtfully as I spoke, and when I was done, he smiled and his eyes brightened as he said, “That is exactly what I want you to do – I want you to feel and to develop your own opinions. Use all that hate to write the essay.” So, I did. It is still one of my most memorable writing pieces. For the first time, I learned what it felt like to have a teacher validate my experience and encourage me to take a deep dive into my interests. While I didn’t realize it at the time, my English teacher was applying student-centered learning practices. He wasn’t teaching to his own agenda or prescribed competencies. I wasn’t being asked to comply, I was being asked to question.

Transformational learning is messy.

It doesn’t neatly check boxes or follow a particular path laid out by the teacher, administration, or district. It requires both curiosity and yielding to the unknown.

Let’s Get Curious

So, what happens in the brain when we are curious?

Research shows that curiosity is a state in which we anticipate external rewards. The parts of the brain that light up when we are curious are a part of the dopaminergic circuit (Gruber, 2015). Dopamine drives both motivation and the learning signal (Willuhn as cited in KNAW, 2023).

Research also suggests that the brain’s reward system “warms up” the memory system, making it easier to encode both direct and incidental information (Gruber, 2015; Shohamy & Wagner, 2015). In other words, learners don’t need to be curious about the exact information. As long as curiosity is enacted, the brain is simply more able to commit experiences to long-term memory.

Join the Beckley Academy Mailing List

How does it feel to be curious?

Now that we know a bit more about the neuroscience of curiosity, let’s venture into how it feels to be curious.

- Try this out.

- I’m going to ask an obscure trivia question that you hopefully don’t know the answer to. We’ll study what happens in the body when we don’t know something but want to. Then, I will tell you the answer, and we will study what happens when our curiosity is satiated. (If you happen to know the answer, try this exercise with something else you have been wondering about but do not know).

- What animal cannot stick out its tongue?

- You may be thinking hard about what animal this might be. But for now, put those thoughts aside. Take a moment to sense into your body as you hold the trivia question in your mind. What do you notice? You might notice a shift in your breathing, a tightness in your muscles, or even a queasiness in your stomach. Whatever you notice, just be curious about it, without trying to change it.

- Try to sit with the sensation of not knowing but wanting to know as long as you can.

- Notice if there are any emotions present. You might feel anxious, annoyed, excited or something else.

- Finally, notice any thoughts that go with your sensations and emotions. If you could put words to the thoughts, what would they be? Maybe, OK, enough of this. Just tell me the answer! Or maybe you’re thinking, I’ll never get it! Whatever thoughts come up, just notice them with an open mind.

- Now scroll down to the bottom of this article to see the answer!

- Now that you know the answer, pay attention to what shifts in your body. You may feel a shift in your breathing, a loosening of muscles, or a shift in sensations.

- Try to sit with the sensation of knowing something new as long as you can.

- Notice what emotions emerge as you experience learning something new. You might feel a sense of pride, relief, joy, or something else. Whatever emotions you notice, just allow them to emerge without trying to change them.

- Finally, notice what thoughts go with your emotions and body sensations. Maybe you had an inkling of the answer and are thinking, “Ah ha! I knew it!” or maybe you’re thinking, “Wow, interesting!” or even, “Wait, are there other animals that can’t stick out their tongues?” Whatever thoughts arise, just observe them without judgment.

In this exercise, you experienced dopamine in two different ways: as a motivator of learning and as a reward.

Curiosity and Risk

The idiom, “Curiosity Killed the Cat” highlights the correlation between curiosity and risk.

Research suggests that the amount of risk needs to be just right to pique curiosity in learners. In a study by Kang et al. (2009), participants were confronted with a trivia question. Participants who exhibited the least amount of curiosity were those who “had no clue about the answer” or were “extremely confident” that they knew the answer (as cited in Kidd & Hayden, 2015). In the case of those participants who had no clue about the answer, there was too much risk to engage in curiosity. For the overly confident participant, there was not enough risk to engage in curiosity. However, for participants who had some idea about the answer but were not totally sure, there was just enough uncertainty to engage with curiosity. These participants were likely to seek out the correct answer (Kang et al., 2009, as cited in Kidd & Hayden, 2015).

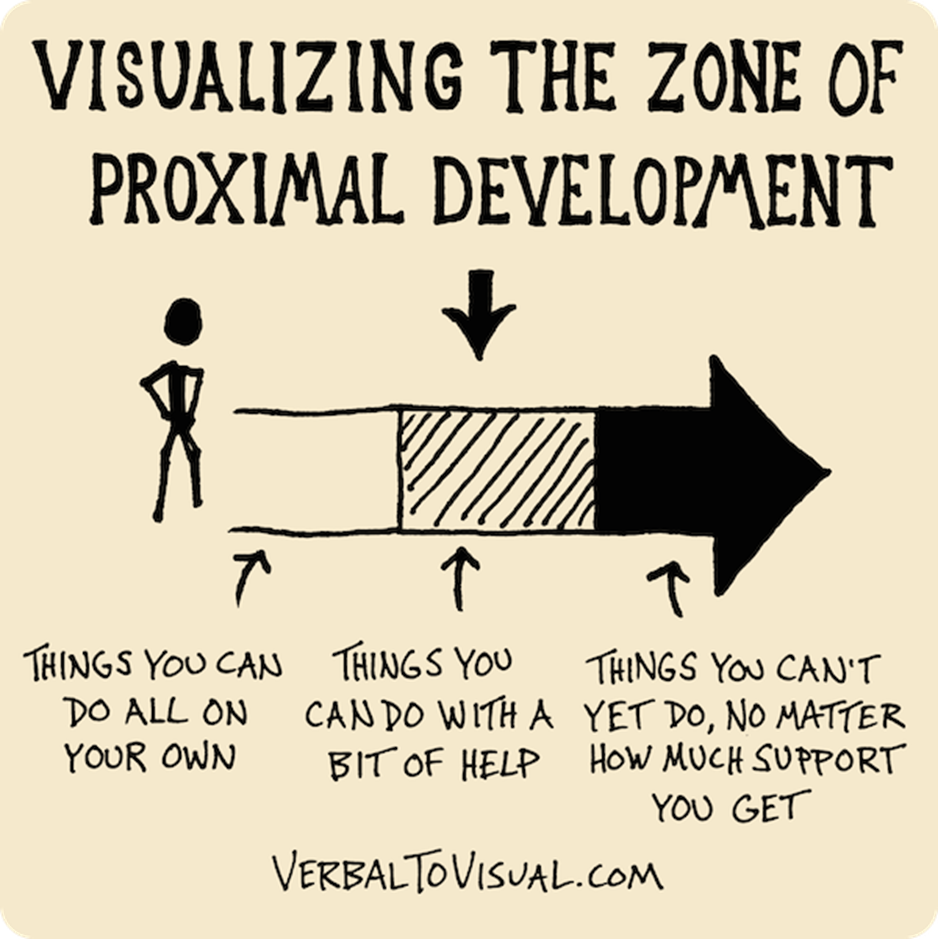

What can we learn from this? One implication is that to foster curiosity in learners, there needs to be some level of uncertainty or risk. Too much certainty in what we already know can stifle curiosity. Too much risk and learners disengage.

One way to think about finding the right amount of risk is through Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development. The zone of proximal development is the difference between what a learner can do without help and what they can do with the guidance and encouragement of a more experienced individual (Shabani et al., 2010). The lens of development also points to the fact that learners need each other and mentors to stretch themselves and gain access to the things they do not know yet.

Another helpful model for finding the right amount of risk is Porges’s polyvagal theory. To fully engage in healthy risk taking that leads to transformation, the parasympathetic nervous system must be engaged. It is from within social engagements, that learners feel calm, connected, and open (Porges, 2017). Curiosity blossoms in social settings where there is a supportive structure that allows learners to engage in experiments, take risks, and test their theories.

For students to engage in transformational learning, they must be willing to yield into the experience. This means letting go of preconceived notions, opening up to new perspectives, and being willing to take risks. In this space of yielding, which is inherently liminal, students can tap into their curiosity and explore the unknown, making connections, and creating insights that go beyond the prescribed material.

Yielding into the Learning Experience

Yielding is the process of letting go and leaning into someone or something else (Bainbridge Cohen, 2018). We can witness yielding, one of five developmental movements, when a child collapses into the arms of a trusted adult, letting go of control and trusting they will be caught.

At the core of yielding is trust. Trust in the process and trust in support. Yielding also happens conceptually, as we grow, when we yield to another’s idea or yield to the unknown. When we yield, we allow something new to emerge.

For transformational learning to occur, students must be willing to yield into the learning experience, to take risks, and to open themselves up to new ideas and perspectives. This requires a shift in the traditional power dynamic between teacher and student. Instead of the teacher holding all the knowledge and doling it out to students, the teacher becomes a facilitator and guide, creating a safe and supportive environment for students to yield into their own learning journey.

Yielding into experience also takes practice. We must help students develop the capacity to sit with discomfort and have compassion for themselves and empathy for others as they push beyond their comfort zones.

In this student-centered approach, the goal is not to meet prescribed competencies, but rather to nurture curiosity and critical thinking skills in students. Students are not just passive receivers of information, but active participants in constructing their own understanding of the world around them. They engage in meaningful and relevant tasks and projects, where they can apply their knowledge and skills to real-world situations. This type of learning empowers students to take ownership of their education and prepares them for a lifetime of learning and growth.

Letting Go of Personal Agendas

For educators to support curiosity and safety that allows learners to yield into the learning experiences, we must be able to set aside our personal agendas. Easier said than done; setting aside our own agendas means first understanding them. This self-work iis critical to identifying implicit biases, our own learned ways of doing and knowing, and how they may be limiting our students’ potential for transformational learning experiences.

It also means letting go of our traditional roles as knowledge dispensers and authority figures.

We must become facilitators, coaches, and co-learners with our students, creating an atmosphere where they feel safe to explore and take risks.

This requires us to relinquish control and trust in the process and in our students’ ability to navigate their learning journey. It may feel uncomfortable at first, but the reward is a classroom full of engaged, curious, and empowered learners.

Practice Letting Go

- Think of something that feels really important to you — something you want your students to know. It might be that you want them to learn how to write a persuasive essay, or you want them to understand a particular historical event.

- Take a few deep breaths and notice any sensations in your body. How do you feel when you think about your students learning this?

- Reflect on why this is important to you. Is it something you wish you knew at their age? Is it something you think they need to know to be successful? Is it something you are required to teach?

- Now, see if you can set the content you believe is important aside. Just for a moment, release your attachment to the idea and allow yourself to be curious about what your students might want to learn. What questions might they have about this topic?

- This exercise might bring up some discomfort or resistance, and that’s okay. Just notice it with curiosity and explore your thoughts and feelings.

The more we practice this type of letting go, the more open we can be to real student-centered transformational learning experiences.

Creating a Culture of Student-Centered Transformational Learning

Creating a culture of student-centered transformational learning involves a shift in mindset and practice for teachers and students. It requires a deeper understanding and implementation of competencies such as curiosity, critical thinking, collaboration, and self-directed learning. It also requires a shift in the traditional power dynamic and the creation of a safe, supportive, and trust-building learning environment.

As educators, we can start by reflecting on our own school experiences as I did at the beginning of this article. Which experiences were the most memorable and impactful? How can we create more of those experiences for our students?

In my own journey as an educator, I have found that when I let go of my own agenda and allow for co-creation with my students, the learning experiences become much more relevant and engaging. When I focus on nurturing curiosity and critical thinking, rather than just meeting competencies, students are more engaged and their learning leads to transformations.

Trivia answer

For the curious, the animal that cannot stick out its tongue is a crocodile. The crocodile’s tongue is attached to the bottom of its mouth by a membrane that holds it in place.

The series will culminate in a community discussion of our theory of education for psychedelic-assisted therapy at Beckley Academy.

All are welcome! Whether you are a learner, educator, or theorist, we’d love to hold space with you.

References

Gruber, M. (2015, November 20). This is Your Brain on Curiosity [Video]. TEDxUCDavisSalon. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SmaTPPB-T_s.

Kidd, C., & Hayden, B. Y. (2015). The Psychology and Neuroscience of Curiosity. Neuron, 88(3), 449–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.010

Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience – KNAW. (2023, June 6). How does dopamine regulate both learning and motivation? ScienceDaily. Retrieved August 17, 2023, from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2023/06/230606111734.html

Porges, S. W. (2018). The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory: The Transformative Power of Feeling Safe (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). W. W. Norton & Company

Shabani, K., Khatib, M., & Ebadi, S. (2010, December). Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development: Instructional implications and teachers’ professional development. English Language Teaching, 3 (4), 237-248. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1081990.pdf

Shohamy, D., & Wagner, A. D. (2008). Integrating memories in the human brain: hippocampal-midbrain encoding of overlapping events. Neuron, 60(2), 378–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.023