Social injustice severs access to resources and community that are essential to fulfilling our basic human needs. With limited access to essential resources like education, healthcare, clean water and air, and fair employment, those who have been excluded by the dominant culture are relegated to perpetuating cycles of poverty and inequality. As educators, we stand at the forefront of addressing social inequity through transformative learning.

Home and Belonging: Cultivating Belonging and Identity in Learning Spaces

Guided-Mindfulness Activity

In our journey to cultivate a sense of belonging and identity within learning spaces, I invite you to join me in a guided-mindfulness activity centered around the concept of “home.” Let’s delve deeper, beyond traditional walls and roofs, and explore what “home” means to you personally.

- I want you to imagine home. What does it mean to you? What pictures play in your mind’s eye? What emotions do you associate with home? What beliefs emerge as you think about home?

- Imagine the scenes that flicker through your consciousness when you think of home. Is it a particular place, filled with specific sights and sounds? Maybe it’s your childhood bedroom, with posters on the walls and a sense of safety nestled in the corners. Perhaps it’s a grandparent’s kitchen, the smell of spices and herbs mingling with the warmth of a stove, laughter echoing off the tiles. Or maybe it’s not a place at all, but a feeling—an embrace from a loved one, the comforting sound of a friend’s voice, a sense of connection that can be carried with you wherever you go.

- Consider the emotions that the word “home” evokes. Is there joy, nostalgia, or perhaps a twinge of sadness for times and places lost? Home might bring a sense of peace and calm, a sanctuary from the outside world, or it could stir up feelings of longing and desire for what once was or what could be.

- Now, extend this concept of home beyond the individual to the community level. Think of the faces in your community, the places where you gather, the activities you engage in together.

- What beliefs emerge as you consider the word “home?” You might notice thoughts like, “Home is a place where I can relax,” or, “I find home in my relationships with others,” or “Home always feels out of reach.” Or something else.

- As the guided-mindfulness activity feels complete, draw your attention to your body. You might notice an impulse or desire to move: to take a deep breath, to wrap your arms around yourself, to get up and shake off the feeling; go ahead and do whatever might feel good right now. When your system settles, reflect upon this exercise.

Consider this:

- In what ways is home concrete for you? In what ways is home fluid, or dynamic for you?

- Does home evoke safety for you, or a more challenging concept, like displacement or discord?

- How does a community create a collective sense of home? How do the streets, parks, schools, and meeting places contribute to a shared home?

- And in what ways does social injustice impact this communal home, fragmenting and fracturing it by denying resources and opportunities to some?

Defining Home

For some, home is a safe haven, a place to retreat and rejuvenate. For others, home is a challenging concept, intertwined with experiences of displacement or discord. It may also be a space of resistance, where identities are forged and personal histories are written against a backdrop of societal expectations.

There are many conceptualizations of home in a diverse and interconnected world.

- Home is fluid. A vast network of delicate yet resilient threads that connect us to one another, to all beings, to the planet, across space and time (Kimmerer, 2013).

- Home is a diaspora. A cultural and emotional connection to a place of origin and a dual awareness of displacement and disconnection (McGavin, 2017).

- Home is a journey. The continual search for where we fit in, the experiences that shape us, and the transformations that happen along the way (Fathi, 2021).

For students who live with poverty, who live with everyday trauma, who have migrated, or fled their home countries to escape war, there may be no physical place that feels like home.

Our challenge as educators is to construct learning environments that serve as homes—spaces where every student feels valued, understood, and connected. Such environments meet foundational needs for belonging and acceptance, empowering all to engage boldly with the challenges and opportunities of our world.

The Guest House

By Rumi; Translated by Coleman Barks (1996)

This being human is a guest house. Every morning a new arrival.

A joy, a depression, a meanness, some momentary awareness comes as an unexpected visitor.

Welcome and entertain them all! Even if they’re a crowd of sorrows, who violently sweep your house empty of its furniture, still, treat each guest honorably. He may be clearing you out for some new delight.

The dark thought, the shame, the malice, meet them at the door laughing, and invite them in.

Be grateful for whoever comes, because each has been sent as a guide from beyond.

Through this expanded conceptualization of home, we see not only a personal refuge but also a potent symbol of what we can achieve in our communities when we commit to equity and justice. By redefining and reclaiming home for those who have been othered, we can begin to unravel the cycles of poverty and inequality that social injustice perpetuates and, instead, cultivate spaces where every individual has an equitable opportunity to thrive.

Join the Beckley Academy Mailing List

Teachers as Change Agents

To support the learners of today and leaders of tomorrow, educators must seek nuanced understandings of social issues impacting diverse learners, historical implications of implicit bias in education, and an educational philosophy rooted in social justice.

The call to transform the purpose of education has been echoed by educational theorists for decades. With the introduction of 21st Century Skills in the early 2000s, we had a framework that promised sustainable and equitable education. Yet, despite the potential this framework promised, meaningful change has been elusive, as noted by Greenhill in 2010. We still face significant challenges in achieving key educational goals. These include ensuring greater transparency and accountability in governmental decision-making (UNESCO, 2012), empowering learners to understand how cultural interactions shape various situations and events (Mansilla & Jackson, 2013, p. 10), and striving for sustainable development that enhances the quality of life for all, while addressing the destructive impacts of war on such progress (UNESCO, 2012).

Attempts to shift the purpose of education have failed because of powerful political forces that aim to maintain the status quo and keep resources and power where they are. In essence, education has become a plutocracy in our modern world, controlled exclusively by the wealthy and, thereby, powerful. One example of this in the United States is the far right’s attempts to make open discussion about systemic racism in school illegal (Kearse, 2021). When teachers broach conversations about the historical context of inequitable access to resources in states such as Tennessee, Missouri, Michigan, and West Virginia, they risk being fired or sued (Kearse, 2021). For learners to thrive in the face of systemic racism and oppression, global-level armed conflict, and a lack of resources essential for life, we must continue to address the historical biases that contribute to inequitable resource distribution.

For education that fosters sustainable and equitable development to take root, educators must embrace their roles as radical agents of change, ready to face any potential challenges this stance may entail.

It is essential to cultivate courage and resilience, standing firm against the formidable injustices that threaten our global community’s survival.

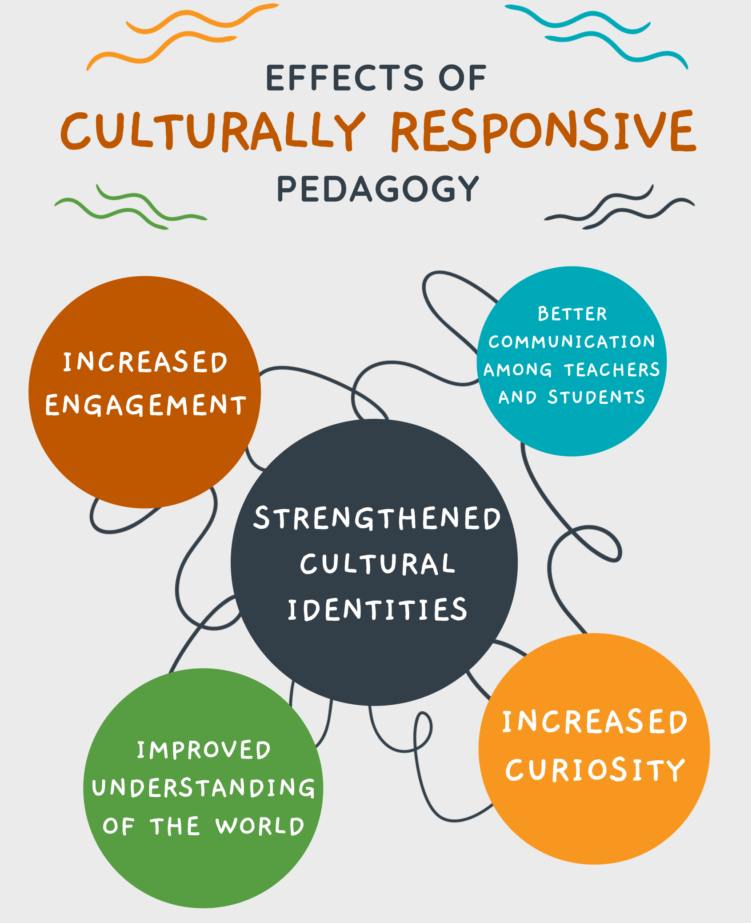

Minimizing Harm Through Culturally Responsive Teaching

Educational practices have historically been rooted in the value systems of dominant cultures, which has led to a hidden curriculum that maintains power imbalances—empowering dominant groups and disempowering non-dominant ones (University of Minnesota Libraries, 2016). Charles R. Lawrence III, a law professor at Georgetown University, articulates the profound effects of systemic racism and oppression within the U.S. educational system, noting stark disparities in how children are taught based on race, class, and financial resources. He observes that students are not only educated in different settings but are also offered different content, spoken to in different ways, and imbued with differing expectations, ultimately preparing them for divergent futures and instilling varied perceptions of their worth (Lawrence, 2006, pp. 712-713).

The need for educational leaders to embrace culturally responsive teaching practices is critical in minimizing these harms. Lack of awareness about the necessity of integrating culturally responsive practices in the classroom can exacerbate the harm, rather than mitigate it.

For instance, Cullen (2016) describes a situation where a white preservice teacher unintentionally reinforced stereotypes about wealth and race by using Bill and Melinda Gates as examples in a discussion on financial planning, unaware of the diverse economic backgrounds of people of color. The example of Bill and Melinda Gates, which was not only an irrelevant example to some of the students of color in the room, but it also perpetuated biases about wealth and whiteness. Cullen explains, “Perhaps it had not occurred to him that there are people of color who are wealthy as well. My impression was that the preservice teacher planned examples that helped him make connections but had not yet developed the insight to realize why his example failed to work within this context” (2016).

Cullen suggests a simply implemented culturally responsive approach — asking students to generate a list of wealthy people from their existing knowledge. By stimulating prior knowledge, educators can elicit enough familiarity to engage students, increase self-efficacy, and support more elaborate encoding of new information. This example highlights the need for educators to engage students with relatable content that reflects their backgrounds to foster engagement and self-efficacy.

Personal and Professional Development

Personal and professional development is essential for educators to implement culturally responsive education and act as agents of social change because it helps to deepen their understandings of their own identities in relationship to society and equips them with skills and knowledge to effectively address and engage with diverse and complex classroom dynamics. Samuels (2018) outlines several key areas where professional development can significantly impact an educator’s ability to facilitate social change:

- Exploring Personal and Professional Identities: Professional development opportunities allow teachers to deeply explore their own beliefs, values, assumptions, dispositions, biases, and experiences related to diversity. This introspective process is crucial because educators’ personal views and experiences can profoundly influence their teaching styles and interactions with students. Understanding and acknowledging their own backgrounds and biases helps educators avoid perpetuating those biases in the classroom.

- Discussing Controversial Topics: By increasing their comfort level and enhancing their skills in handling sensitive or controversial topics, educators can lead more meaningful and impactful discussions in their classrooms. Such discussions are essential for broadening students’ perspectives and fostering a critical understanding of societal issues, thereby preparing students to engage with the world in a thoughtful and informed manner.

- Learning and Implementing Inclusive Strategies: Gaining knowledge of inclusive pedagogical strategies, such as creating an inclusive environment, ensuring relevance and accessibility of content, using inclusive language, and ensuring representation in the classroom, and considering how to integrate these approaches effectively into their teaching practice is another critical aspect of professional development. This enables educators to create learning environments that support all students, regardless of their diverse backgrounds, thereby promoting equity in educational outcomes.

- Fostering an Inclusive Classroom Climate: Engaging in ongoing dialogue about how to develop and maintain an inclusive classroom culture is vital. This aspect of professional development helps educators implement practices that reinforce the dignity and value of every student, which is essential for nurturing a supportive and empathetic community within the classroom.

Personal and professional growth is not just about enhancing their teaching skills; it’s about transforming them into catalysts for social change who are equipped to challenge the status quo and inspire a new generation of thinkers and leaders.

Through such development, educators can more effectively translate the principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion into practical action, thereby contributing to a more just and understanding society.

Embodying Anti-racism: Social Justice in Action

Embodied antiracism represents a crucial methodology in education for social justice, urging educators to become transformative agents through a deep, personal exploration of implicit biases. Drawing from trauma theory, which highlights the role of somatic, affective, and cognitive experiences in shaping behavior, embodied learning involves recognizing and modifying these unconscious responses to external stimuli (Ogden & Fisher, 2015). For instance, Helen Ngo’s phenomenological study underscores the somatic level of racism, as seen when individuals respond to racialized situations with fear or nervousness, often resulting from societal stereotypes (Ngo, 2012). Similarly, Menakem (2017) emphasizes that real change requires moving beyond cognitive understanding to a visceral confrontation with one’s biases. This is echoed by Barrett (2017), who points out that our immediate, unconscious reactions often bypass rational thought. Through embodied learning, educators can tap into their somatic responses to challenge and transform these implicit biases, promoting a genuinely inclusive and just educational environment.

Strategies for a Culturally Responsive Classroom

Critical Race Theory: Measuring Inclusivity in Education

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a theoretical framework that examines the relationship between race, racism, and power. It originated in the legal field and has since expanded into other areas, including education and psychology. This framework not only identifies but also seeks to dismantle the legal and societal structures that uphold racial inequality, advocating for profound societal reform to achieve true justice (Hatch, 2015).

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is an invaluable tool for educators to engage in self-reflection and assess their teaching methods, especially in terms of understanding and addressing race and inequality. By implementing CRT, teachers are encouraged to critically examine their teaching approaches and underlying assumptions, fostering more inclusive and effective educational strategies.

In a culturally responsive classroom, teachers are urged to continually evaluate their biases and the systemic structures within which they operate. Kwame Sarfo-Mensah’s resource underscores this by posing reflective questions like, “Are you making the conscious effort to continually check your implicit bias at the door when teaching, engaging with, and disciplining your students of color?” This process of self-assessment is essential for educators to recognize their potential biases and understand their impacts on teaching.

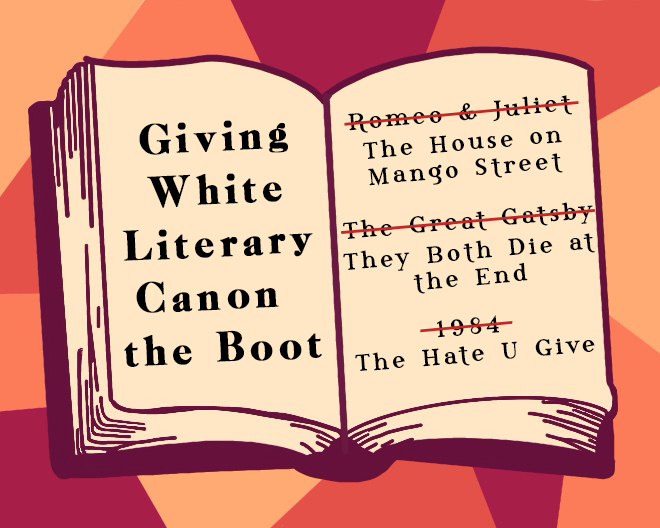

CRT helps educators to creatively address potentially biased or outdated curriculum content. It calls for curiosity and innovation to cultivate culturally relevant teaching methods that respect and reflect the diverse experiences of students. This may involve a reevaluation of how historical events are taught, discussions about the contexts of literary works, or the inclusion of contemporary issues that resonate with students’ lives today.

As a tool for self-reflection and self-assessment, CRT helps educators become more cognizant of the societal and institutional dynamics of race, empowering them to transform their classrooms into inclusive spaces for critical inquiry. This approach benefits all students by promoting a deeper respect and understanding of diverse perspectives and histories.

Promoting Authentic Dialogue

Creating a safe and supportive environment for authentic dialogue is fundamental to a culturally responsive classroom. Paulo Freire (2017) described this as “authentic reflection” and “critical and liberating dialogue,” enabling participants to “transcend limit-situations” (p.102). Authentic dialogue allows educators and students to challenge the status quo, question dominant cultural narratives, and forge counter-narratives. Samuels (2018) emphasizes the importance of addressing the “repetition of sameness,” which perpetuates harmful historical biases (p. 46). Such dialogue ensures that culturally responsive teaching methods are deeply integrated, not just superficially applied, and focus on using education to address societal power imbalances and oppression (Cullen, 2016).

Diversifying Representation in the Classroom

Increasing diversity, inclusion, and cultural awareness in the classroom can be achieved by providing role models and diverse examples, as noted by Ruggs and Hebl (2012) who state, “seeing successful role models who are similar to themselves helps students build confidence that they too can be successful in that domain” (p. 5). Reimers (2017) argues that all students deserve to see themselves represented in the curriculum, and calls for educators to diversify representation in course content (Katz & Sokal, 2016, p. 43). For instance, in an English Literature class, rather than exclusively teaching the traditional white, Western canon, educators might include a variety of works such as The House on Mango Street, Middlesex, Brown Girl, Brownstones, Invisible Man, Reading Lolita in Tehran, and the Bell Jar.

Value and Belonging

Implementing culturally responsive teaching practices enhances the perceived value of each student, fostering a sense of belonging and motivation. Stanford and Reeves (2009) highlight that “a learner’s conviction that he or she is valued by a teacher becomes a potent invitation to take the risk implicit in the learning process” (p. 7). This sense of value is reinforced by counter-storytelling, which elevates the voices of those often silenced or ignored in mainstream narratives, thereby enhancing psychological safety and belonging for all students.

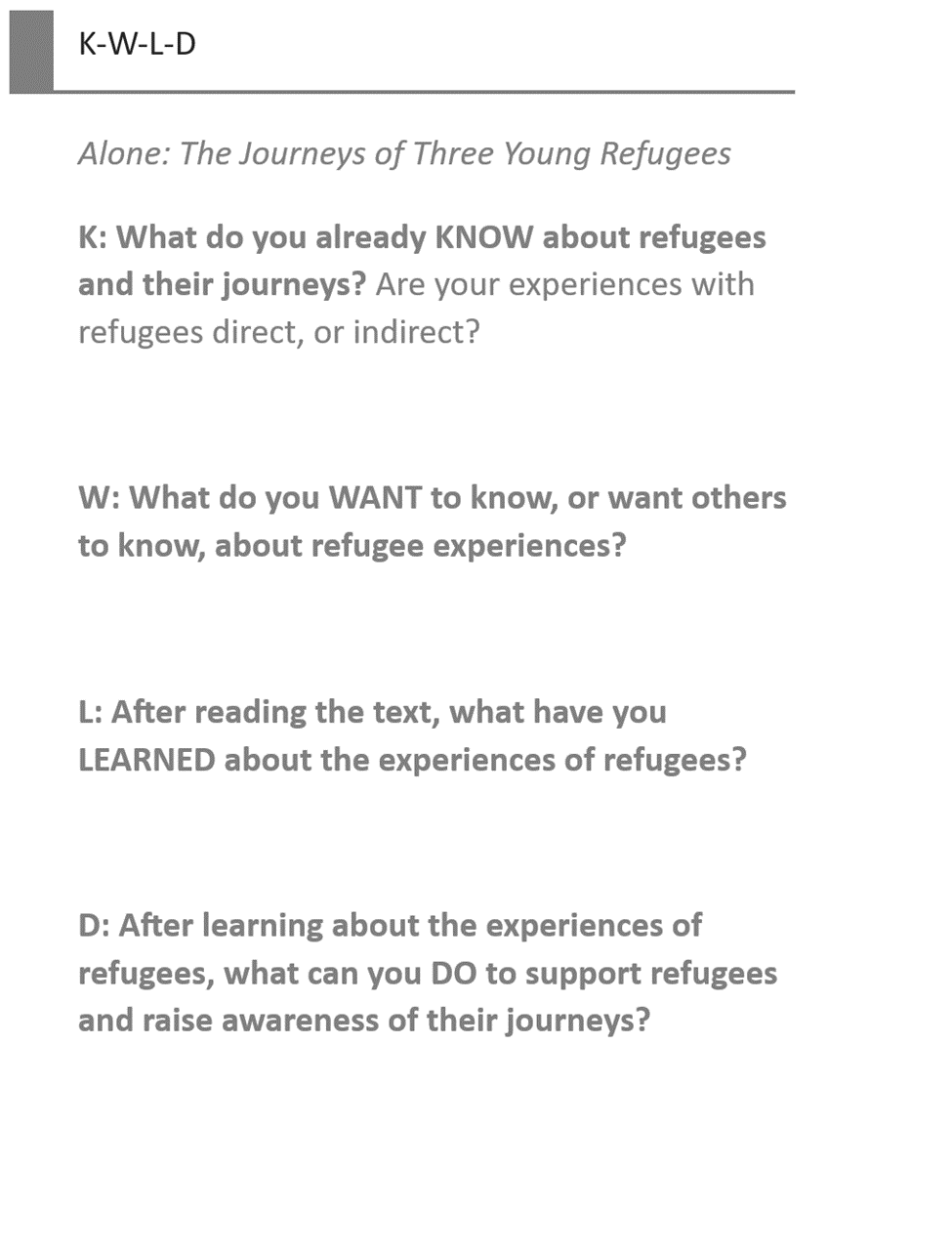

Encouraging Action: K-W-L-D

In this adaptation of the familiar K-W-L (Know-Want to know-Learned) model, I’ve added an additional reflective component that focuses on what learners will Do (D) with the knowledge they’ve acquired.

The K-W-L-D strategy is inherently supportive of culturally responsive teaching and promotes social justice action by integrating several key elements:

Acknowledging and Valuing Learner Backgrounds

- Know (K): This initial phase allows students to express what they already know, elevating the value of the diverse cultural and experiential backgrounds of learners.

Encouraging Curiosity and Direct Engagement

- Want to know (W): This stage encourages students to inquire and identify gaps in their knowledge, which can be particularly empowering for students, as it places their questions and interests at the center of the learning process. By encouraging students to articulate their own learning objectives, they are more likely to see the relevance of their education to their lives and communities.

Building Knowledge and Critical Awareness

- Learned (L): After exploring the topic, students reflect on what they have learned. This stage helps consolidate new knowledge and skills, integrating them with students’ prior understanding and experiences. This phase supports the development of critical consciousness—a key goal of socially just education—by helping students synthesize new information in ways that are relevant to their cultural perspectives and personal identities.

Prompting Action and Advocacy

- Do (D): Perhaps the most significant addition to the traditional model, this component asks students to consider how they can apply their new knowledge to initiate change. This action-oriented phase encourages students to move beyond the classroom and engage in social justice efforts that are personally meaningful. The “Do” phase aligns directly with the goals of culturally responsive teaching by actively promoting social justice. This phase empowers students to use their education as a tool for real-world impact, advocating for themselves and their communities.

By incorporating these elements, your KWLD strategy does more than educate; it activates. It transforms the classroom into a dynamic space where education is directly linked to social empowerment and action.

Cultivating Community

Community within educational settings plays a crucial role in enriching both teaching and learning experiences. For educators, being part of a supportive community offers invaluable opportunities for reflection on teaching practices, mentorship, and exposure to diverse pedagogical ideas. Engaging in dialogue with peers creates a reflective practice environment where teachers can share challenges, successes, and insights, thus fostering professional growth and innovation. Mentorship from more experienced colleagues can guide newer teachers through the complexities of classroom dynamics and curriculum nuances. Exposure to diverse educational philosophies and strategies within a community enhances teachers’ ability to adapt and innovate in their own classrooms.

For students, a strong sense of community in school contributes significantly to their sense of belonging and emotional well-being. When students feel they are part of a caring and inclusive community, their engagement and motivation to learn increase. This environment supports not only academic achievement but also the development of social skills and self-esteem. Community fosters a network of peer support where students can feel safe to express themselves and explore their identities. It acts as a nurturing ground for young individuals to form connections, appreciate diverse perspectives, and collaborate effectively, which are essential skills for their future endeavors in an increasingly interconnected world. By cultivating such communities, schools can significantly enhance the educational experience and prepare students and teachers alike for a broader engagement with the world around them.

Through education focused on social justice, we not only transform ourselves and our students but also contribute to broader societal change. By fostering inclusive, mindful, and critically engaging spaces, we prepare our learners not just to thrive in the world but to reshape it. By embedding principles of equity and justice into our teaching, we initiate a ripple effect that extends beyond individual classrooms, advocating for systemic change and nurturing a more just society.

As agents of change, educators are equipped to face challenges and to advocate for a world where every individual can thrive. In doing so, we uphold John Dewey’s (1926) vision of education as “the fundamental method of social progress and reform,” driving forward toward a future where education is truly a catalyst for societal improvement and equity.

References

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: the secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Cullen. K.A. (2016, March 21). Culturally responsive disciplinary literacy strategies instruction. In Crandall, B. R., Lewis, E., Stevens, E.Y., Robertson, J. M., O’Toole. J. E., Cullen, K.A., …McQuitty. V. (Ed.), Steps to success: Crossing the bridge between literacy research and practice. Open SUNY Textbooks (pp. 173 – 190). https://textbooks.opensuny.org/steps-to-success/

Dewey, J. (1926). My pedagogic creed. Journal of Education, 104(21), 542–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205742610402107

Fathi, M. (2021). Home-in-migration: Some critical reflections on temporal, spatial and sensorial perspectives. Ethnicities, 21(5), 979-993. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968211007462

Freire, P. (2017). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1970 by The Continuum Publishing Company).

Gardner, D. (2024). ‘K-W-L-D: Alone: The Journeys of Three Young Refugees. [IMAGE].

Perez-Granados, K. (2020, December 19). Giving White Literary Canon the Boot [Image]. Daily Nexus. https://dailynexus.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/dailynexus/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/15130812/white-lit.jpg

Hatch, A. (2015). Critical Race Theory. Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405165518.WBEOSC206.PUB2.

Katz, J., & Sokal, L. (2016). Universal design for learning as a bridge to inclusion: A qualitative report of student voices. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 12(2), 36-63. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1118092.pdf

Kimmerer, R. W. (2015). Braiding sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions.

Lawrence, C. R. (2006). Who Is the Child Left Behind? The Racial Meaning of the New School Reform. Georgetown Law Faculty Publications and Other Works., 341. https://doi.org/https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/34

McGavin, K. (2017). (Be)Longings: Diasporic Pacific Islanders and the meaning of home. In TAYLOR J. & LEE H. (Eds.), Mobilities of Return: Pacific Perspectives (pp. 123-146). Australia: ANU Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt20krz1j.8

Menakem, R. (2017). My grandmother’s hands. Central Recovery Press.

Ngo, H. (2019). Habits of racism: A phenomenology of racism and racialized embodiment. New York, NY: Lexington Books.

Ogden, P., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor psychotherapy: Interventions for trauma and attachment. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Reimers, F. (2017, August 03). Rediscovering the cosmopolitan moral purpose of education. Retrieved February 22, 2018, from https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/rediscovering-the-cosmopolitan-moral-purpose-of-education/.

Ruggs, E. & Hebl, M. (2012). Literature overview: Diversity, inclusion, and cultural awareness for classroom and outreach education. In B, Bogue., & E, Cady (Eds.). Apply research to practice. http://teach.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ARP_DiversityInclusionCulturalAwareness_Overview.pdf

Rūmī, & Barks, C. (1996). The essential Rumi. 1st HarperCollins paperback ed. San Francisco, CA, Harper.

Samuels, A. J. (2018). Exploring culturally responsive pedagogy: Teachers’ perspectives on fostering equitable and inclusive classrooms. SRATE Journal, 27(1), 22-30. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1166706.pdf

Sarfo-Mensah, K. (2021, July 11). Twitter. https://twitter.com/identityshaper/status/1414171618780356608.

Stanford, B., & Reeves, S. (2009). Making it happen: Using differentiated instruction, retrofit framework, and universal design for learning. TEACHING Exceptional Children Plus, 5(6), 1-9. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ967757.pdf

University of Texas at Austin. (n.d.). Culturally Responsive Teaching. [Image]. Retrieved from https://encrypted-tbn2.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcSfycEh70G35QszoyNcGryjJ2A68audOV3K_iaDE02sB1V1JF3O

University of Minnesota Libraries. (2016, March 25). 11.2 Sociological Perspectives on Education. Social Problems. https://open.lib.umn.edu/socialproblems/chapter/11-2-sociological-perspectives-on-education

More about this Series

A former student of mine reached out to me through social media. She wanted to let me know that she decided to pursue a career in social justice law in part because of the experiences she had in my English class over a decade ago. Rather than swell with pride— okay, I did shed a happy tear or two— I started wondering, “What’s the recipe for education that is engaging enough to change lives?”

My educational background in art, literature, and social justice, and my diverse professional experiences in education, first teaching students learning differences, and in the last decade, building courses in psychology and mental health modalities for post-grad learners, have illuminated several theories that, applied skillfully, engage learners, making learning meaningful, and create just the right amount of challenge for diverse learners.

In this five-part newsletter series, we will cover topics of theory and practice related to education and mental health. The series will culminate in a community discussion of our theory of education for psychedelic-assisted therapy at Beckley Academy.

All are welcome! Whether you are a learner, educator, or theorist, we’d love to hold space with you.